Brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) use neurophysiological signals to control an external device in real-time, without the involvement of the musculoskeletal system. During the past few years, technological advances in the field of BCI suggest that it is possible to decode speech related features directly from neural signals. These speech-neuroprostheses, once functioning, will provide a new channel of communication and rehabilitative solutions for patients that have lost the ability to communicate due to neurological disorders such as aphasia and locked-in syndrome.

Pro Event Calendar

The Brainhack will start on Thursday December 1st late afternoon with project pitches and teams creation. The following two days, Friday 2nd and Saturday 3rd, will be full of hacking, but also breaks in the form of talks on cutting edge or offbeat neuroimaging research

There are large individual differences in speech and language processing skills at different levels of the linguistic hierarchy, and these are likely modulated by experience-dependent plasticity but also by possible differences in innate predisposition. In this talk, I will provide an overview of our work which supports, on the one hand, the influence of learning and experience on the brain (i.e. brain plasticity), and on the other hand the possible role of predisposition in determining individual differences in specific language and auditory (e.g., musical) skills. More specifically, I will describe ongoing and planned work on nature vs nurture influences on the size and shape of the auditory cortex, and its relation to individual differences in auditory processing in the context of language and music. Future directions will involve elucidating brain functional / structural mechanisms beyond the auditory cortex that may be involved in conferring resilience, or compensatory potential, in the context of development and acquired language disorders.

The studies of the evolution of language and culture are intertwined. Often, the same mechanisms – the usual suspects such as imitation – are argued to be at the heart of the evolution of both. In my own research, I have variously addressed aspects of behaviour such as intentionality, efficiency, or affect, that also appear involved in the evolution of both phenomena. In this talk, I will aim to take a step back and synthesize these different threads to offer a path to highlight the differences and similarities, and a way forward to investigate the co-evolution of culture and language.

Comparative research in animal communication has revealed that many elements of language can be found in other species, but also how human language is nevertheless unique compared to the communication systems of other animals. Moreover, we increasingly understand how co-evolutionary feedback processes may have led to fully-fledged language once an initial threshold of becoming more communicative was passed. What is still poorly understood, however, is why this initial step occurred: Why was it our ancestors, rather than any other ape species, to take this evolutionary trajectory that would eventually lead to language? In this talk, I will explore the role of cooperative breeding, i.e. the systematic reliance of mothers on other group members to successfully raise offspring. Cooperative breeding has convergently evolved in humans and callitrichid monkeys, but is absent in other primates, most notably in all other apes. The core argument is that this breeding system sets the stage for increased interdependence and cooperativeness. Implemented in a great-ape like cognitive system – as the one of our ancestors – this likely had the potential to lift communicative motivation above the necessary threshold to allow language to evolve. I will use comparative and developmental data to exemplify this idea, and end by comparing it to alternative approaches that aim at explaining the early beginnings of language evolution.

The most caudal part of the left inferior frontal gyrus in the human brain – better known as Broca\’s area – is probably one of the most highly regarded and studied cortical regions. It became well known during the last century when it was incorrectly referred to as the \”expressive language center\” of the brain. However, meanwhile it is widely accepted that Broca\’s area subserves a multitude of cognitive, sensory and motor functions. Some of them are related to language while others are not. Much less is known about the contralateral region in the right hemisphere – dubbed as \”Broca\’s homologue\”. There does almost no explicit research exist that has so far thoroughly and explicitely looked in the functional neuroanatomy of this brain region even though brain imaging studies during the last two decades have occasionally reported its involvement in language and cognitive-motor mechanisms. Interestingly, there seem to be neuroanatomical pecularities that make Broca\’s homologue a special case in the human brain compared to the brain of great apes (which does not to the same extent hold for Broca\’s area in the left hemisphere).

The talk will give an overview on what we know about the functional role and neuroanatomical architecture of Broca\’s homologue. Is there a rightward asymmetry for specific neuronal measurements in the human brain? How is Broca\’s homologe connected to a) other ipsilateral perisylvian areas b) subcortical nuclei, namely the basal ganglia, and c) the controlateral frontal operculum? What might have been the role of Broca\’s homologue for the evolution of motor and vocal control? To what extent might higher cognition be supported by Broca\’s homologue? What do we know about the changes this area had undergone during human brain development?

In this talk I aim for setting up scientific questions for an interdisciplinary research programme for the second NCCR period.

One of the great unknowns in language evolution is the transition from unstructured sign combination to grammatical structure. This paper investigates the central — while hitherto overlooked — role of functor–argument metaphor in this transition. This type of metaphor pervades modern language, but is absent in animal communication. It arises from the semantic clash between the default meanings of terms. Functor–argument metaphor became logically possible in protolanguage once sufficient vocabulary and basic compositionality arose to allow for novel combinations of terms. For example, the verb to hide, a functor, could be combined not only with a concrete, spatial entity like food as its argument, but also with an abstract, non-spatial one like anger. Through this clash, to hide is reinterpreted as a metaphorical action.

The central requirement for functor–argument metaphor is compositional meaning construction in the language. At the same time, such metaphor transcends compositionality, forcing nonliteral interpretations. We argue that functor–argument metaphor led the development of protolanguage into fully-fledged language in multiple ways. Not only did it expand expressiveness, but it drove the development of syntax, including the conventionalization and fixation of word order, the development of demonstratives, and grammaticalization. Thus, functor–argument metaphor bridges multiple gaps in the trajectory from protolanguage to the elaborate grammatical structures of fully-fledged modern human languages.

The conference will take place on November 14th and 15th in Zürich, in the historic building of the University of Zurich located in Rämistrasse 59. The full event will also be streamed for those attending online.

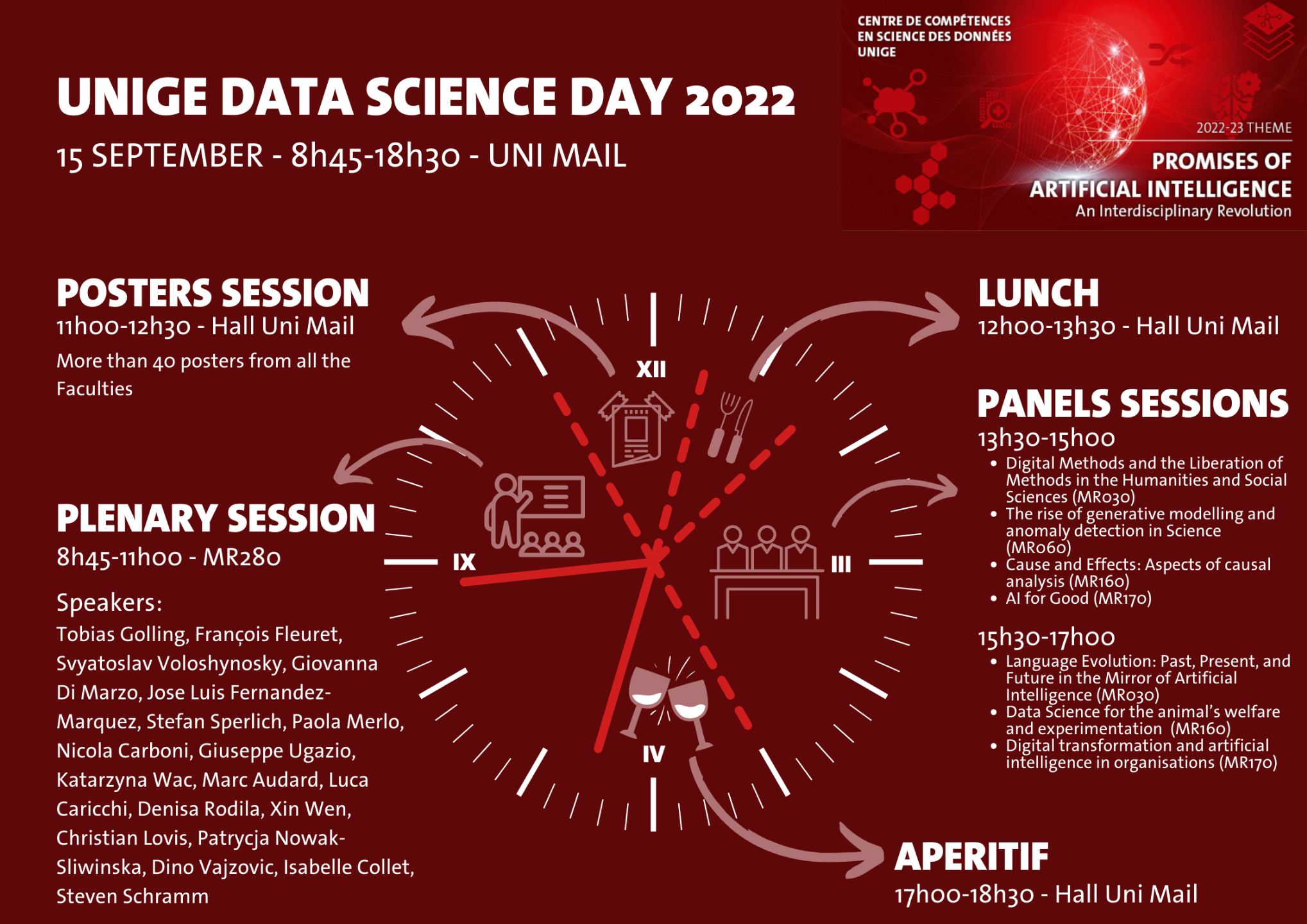

The UNIGE Data Science Day is a scientific symposium for researchers at the UNIGE, which takes place at the beginning of the academic year.

Each year, the CCSD stimulates a collective reflection on a particular theme. This reflection is introduced during the UNIGE Data Science Day and continued in the framework of other activities launched by the Center throughout the year. This theme is intended to be precise enough to encourage a significant scientific contribution and a rich dialogue, but also transversal enough to allow for interdisciplinarity.

Language endangerment is a topic of concern and the interest in language documentation has grown (Himmelmann 1998, 2006; Thieberger 2020). With the technological advent language documentation has extended to include more speech data. However, the number of instrumental studies dealing with the acoustic characteristics of under-documented languages remains relatively small. This workshop offers a forum for the discussion of the experimental study of Speech Units and aims at providing training for those interested in engaging with the topic.